Sunday 16 september 2018

Oslo

After seeing the Viking ships, we went to the Fram museum, which also houses the Gjoa. It was so good that it exhausted us, and now ranks way up there with other museums that knocked us out. In a very good way.

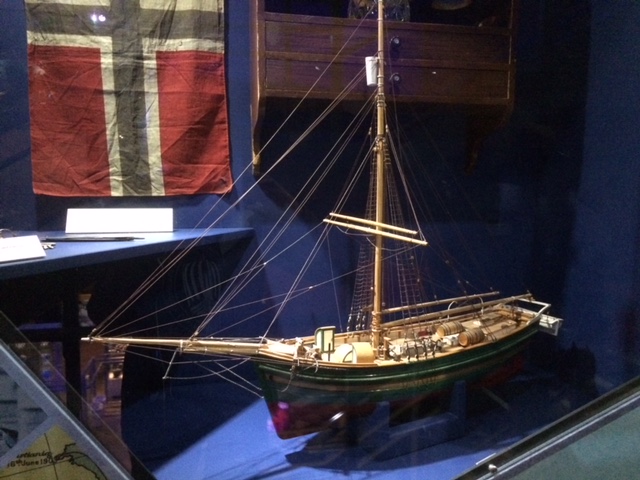

We knew a fair amount about Roald Amundsen and the South Pole, but not as much about his predecessor and mentor, Fridtjof Nansen, a very important Arctic explorer in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His sailing ship the Fram (“forward”) is a wooden icebreaker . . . or maybe “ice survivor” is a better term. Nansen designed it to withstand the pressure of sea ice so that he could use it in his explorations. Here’s a model:

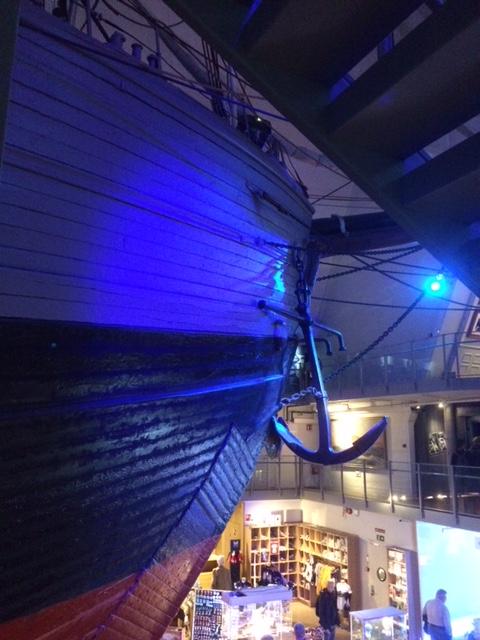

and here’s the side of the real thing, in the museum. I hope you can get a sense of the sizes of both the ship and the three-story room in which it sits.

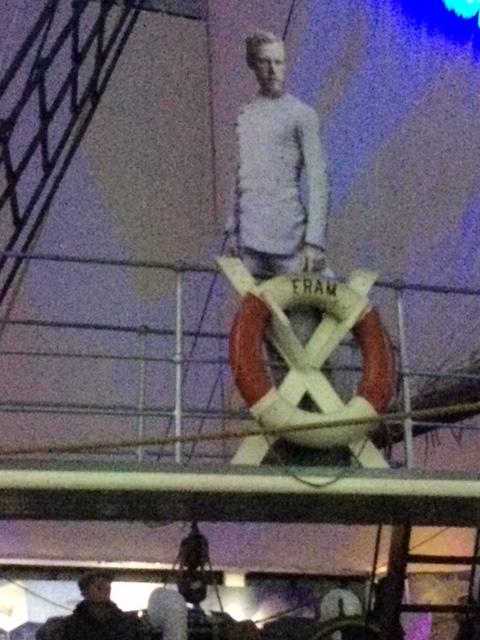

Visitors can go aboard the ship and look around, which is very cool. Here’s a cardboard Nansen standing on deck:

I still have a lot to learn about Nansen’s achievements other than crossing Greenland and coming closer to the North Pole than anyone had previously. But the Fram also took Roald Amundsen and his crew to the shores (?) of Antarctica, where he reached the South Pole in 1911 before anyone else, notably Robert Scott.

Earlier, Amundsen had gone the other way. He took the Gjoa through the Northwest Passage; it was the first ship to do so. Here’s the Gjoa in the museum:

(under brighter lights than the Fram).

That expedition took three years (1903-06), during which they spent two or three winters in the ice. Amundsen took advantage of this time to become good friends with the native Netsilik, an Inuit group. They taught the Norwegians a tremendous amount about surviving in the Arctic, and Amundsen brought back photos and copious records of the education. We saw some of them in the National History Museum here on Saturday. Here’s a mockup igloo constructed from his description:

Having studied hard, Amundsen really knew what he was doing when he headed south in the Fram. He had learned from the Netsilik about food, clothing, shelter, dogs, sleds, and skis. In contrast, the British expedition leader Robert Scott had less experience and thoroughly untested equipment when he set off in what had become the race to the South Pole. (Read The Race to the End of the Earth for the whole story. Spoiler alert: Amundsen reached the pole 33 days before Scott, and Scott’s whole team died on the way back to their base.)

The museum makes a big point of comparing Amundsen’s and Scott’s expeditions. The Norwegian team was not only better equipped and more experienced — Scott took some Navy officers who bought their way onto the British team, never having been in polar conditions — they also had a great leader. Amundsen insisted on being in command of the scientific work as well as the navigation and daily operations, but he lived with his men, shared his plans*, and sought their opinions to improve his decisions. Scott did little or none of this; the officers and men had separate eating and sleeping quarters, and Scott didn’t even tell his officers about his decisions until they became his orders, no discussion allowed. Amundsen brought sleds and dogs, but Scott brought Shetland ponies, some dogs, and motorized sledges that never worked. (Fortunately for the British and the crew of the Endurance, Ernest Shackleton was not like Scott, but that’s another story.)

I think management courses should include required reading on these expeditions.

* For reasons I can’t recount, Amundsen’s stated plan was to make another Arctic exploration, though he knew he was headed for the South Pole. He told the crew they were going to Antarctica only after they had reached the last port at which men could leave if they didn’t like going south.