13 september 2023, London

I suppose one could have a fascinating and active week in London without ever entering a museum. Restaurants, theatre, concerts, pub crawls, garden strolls, cricket matches, and the Changing of the Guard could keep one busy and entertained. But Dan and I would not be that one.

The British Museum was on our list for this trip, if only for the Sutton Hoo helmet. It was part of a hoard of objects from about 600 AD, an Anglo-Saxon treasure trove including jewels, silver pieces, and weapons. This was all buried in the hull of a 90-foot long ship. We have now admired this helmet on three separate visits to the Museum over the years.

We like museums. We like all the information surounding the objects on display and we appreciate the scholarship that supports the iceberg-tips of description, someone’s selection of facts to pass on to us from the volumes of data. We’re always impressed when displays are clear, descriptions are legible, pointers can be followed, rooms are numbered, maps relate to physical reality, etc.

Of all the museums we visited on this trip, the Museum of Natural History stands out for a reason I did not expect. (Wait for it.) it’s huge, even on the scale of Big Important Places in London, and its collections cover everything you think Natural History should include. The entry hall has a whale skeleton hanging from the ceiling.

Some spaces, like the Mineral Hall, remind me of the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973, when it was all display cases you leaned over to read about the artifacts. In this case, it’s a dazzling array (no kidding) of rocks.

Plenty of displays are much more immediately engaging, like this one of the Pangolin.

So there’s descriptive and engaging. I don’t have any photos of the exhibits that aim to be immersive, because I don’t like them much. Here in Natural History, those would include dinosaurs and geological disasters — earthquakes and volcanoes. Loud noises, flashing lights, and shaky floors can be effective; they just don’t usually work for me. This “immersiveness,” which at its worst panders to kids on sugar, was the only thing that put me off.

The Victoria and Albert Museum is another immense edifice full of more than anyone can absorb, and coming to it after Natural History — literally across the street — we needed only a small dose. Fortunately for us, many of the treasures of the ancient world, medieval Europe, and the Italian Renaissance can be viewed in a very compact space, called the Cast Court. (It must have been a bit more spread out at some time.) Here Victorian visitors could see replicas of objects whose originals were far away.

On from the past, into the present and future, the Design Museum was new to us, and it’s a hit. This is the Head of Invention as you approach.

Inside, it’s dramatic, but the public display spaces are not dauntingly huge.

One floor is currently focused on How To Build A Low-Carbon Home. The top floor’s permanent exhibit is all about the Designer, the Maker, and the User. It’s a tour of mostly product design and its importance to people. I didn’t see a lot of detail about process steps (research, prototyping, testing, revising). But there’s definitely a breadth of purpose: from new Tube cars to graphic design of transportation signage to all kinds of consumer products, especially personal technology: Walkmans, iPods, selectric typewriters, cameras, phones, 3-D printing. There were a few displays on fashion.

In case you didn’t know it, your Low-Carbon home can take advantage of wood, stone, and straw (broadly speaking) as affordable and sustainable alternatives to steel, concrete, and plastic. Dan found this group of displays more aspirational than he liked, with only a few real-world examples. I found it inspirational, with references to existing sources and beneficial trade-offs.

One question explored in the upper-floor exhibits was about the purpose of design. Should it make things more efficient? Support memorable branding and commercial success? Open the door to more effective control of the environment, including other people? Is obsolescence a form of progress? (By the way, did you reload your fingernails?)

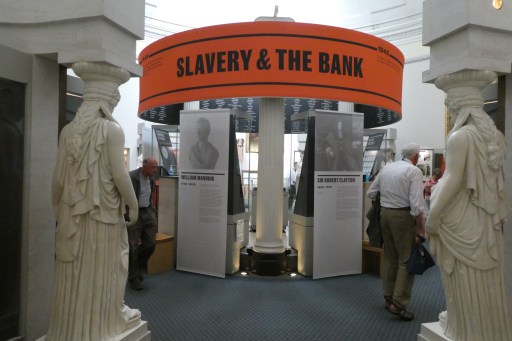

It’s no big surprise when a museum focused on design asks questions about purpose and effect. When we went to the Museum of the Bank of England, however, we did not expect to have this exhibit slammed in the face of visitors:

How can a museum display be sobering, depressing, and admirable all at the same time? No noise or flashing lights here, just painful history from an unexpected source, admitting deep complicity and challenging the visitor to reflect.